Why humans care for the bodies of the deceased

In tracing the history and culture of corpses, a new book shows the importance of remembrance to our species. The ancient Greek Cynic philosopher Diogenes was extreme in a lot of ways. He deliberately lived on the street, and, in accordance with his teachings that people should not be embarrassed to do private things in public, was said to defecate and masturbate openly in front of others. Plato called him “a Socrates gone mad.” Shocking right to the end, he told his friends that when he died, he didn’t want to be buried. He wanted them to throw his body over the city wall, where it could be devoured by animals.“What harm then can the mangling of wild beasts do me if I am without consciousness?” he asked.

What is a dead body but an empty shell?, he’s asking. What does it matter what happens to it? These are also the questions that the University of California, Berkeley, history professor Thomas Laqueur asks in his new book The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains.

“Diogenes was right,” he writes, “but also existentially wrong.”

Every man, Weever writes, “desires a perpetuity after his death.” Without this idea “man could never have awakened in him the desire to live in the remembrance of his fellows.” And without it, human life in the shadow of death would be unbearable and unrecognizable: “the social affections could not have unfolded themselves un-countenanced by the faith that Man is an immortal being.” Our love for one another differs from the love animals might feel for one another in that an animal perishes in the field without “anticipating the sorrow with which is associates will bemoan his death,” whereas we “wish to be remembered by our friends.” Naming the dead, like care for their bodies, is seen as a way to keep them among the living. And maybe it is a way around Diogenes.

So yes, Diogenes, the body is technically nothing once void of its soul, or consciousness, or however one conceives of the essence of a person. We get it. But it’s a physical emblem of that person, and in caring for it, we offer the person’s memory a chance to linger, as we hope our own will.

Even if physical death is quick and final, social death takes time. And through communal effort, people offer each other the chance for their names to last a little longer on Earth than their bodies do. “There is also another way to construe the dead,” Laqueur writes: “As social beings, as creatures who need to be eased out of this world and settled safely into the next and into memory.”

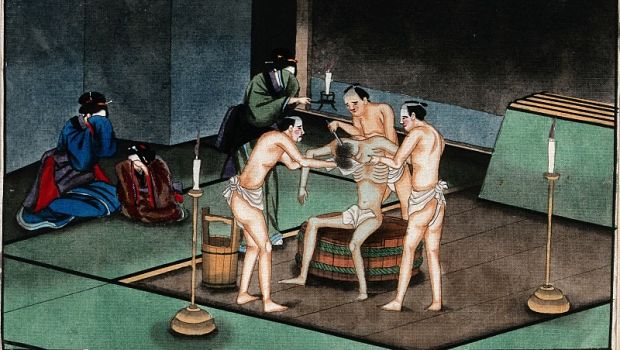

Image: Wellcome Library, London. Japanese funeral customs: two attendants wearing loin-cloths support the body of a dead man while a third shaves his head. Watercolour, ca. 1880.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.